I remember the moment I died.

I was prowling in the high grasses, eyes keen on the wildebeest calf separated from its herd. I was delirious from weeks of hunger and my limbs trembled, rustling the dry grass stalks. If I failed the hunt I would starve, and my two cubs, hidden in a felled tree trunk, would be eaten by the hyenas that lurk around the outskirts of the serengeti. With the last of my energy, I steadied my legs in the soil and prepared my ambush. The young wildebeest stood wide-eyed and dumb, grazing in the open savanna. Its neck was bare, and I listened to the throbbing blood running through its neck, the sound of salvation for my kin.

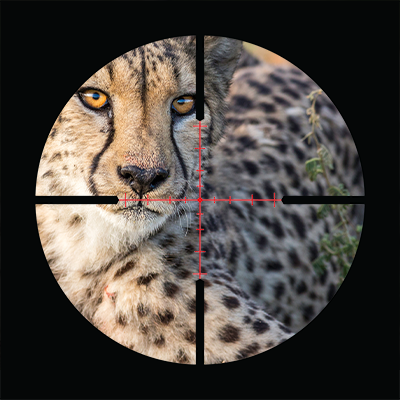

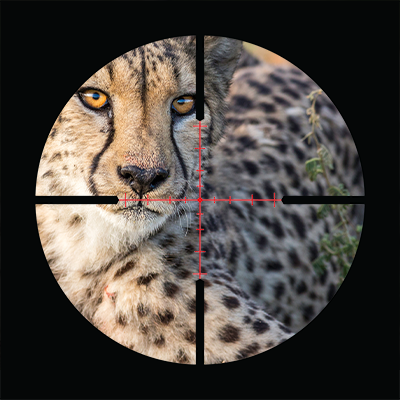

Perhaps it was my hunger, exhaustion, or focus on the wildebeest, but I failed to notice the clumsy footsteps crunching the grass behind me. My prey ran off and I collapsed, knowing my life was over. I prayed for the privilege of a peaceful death by starvation, but I was not even granted this, for as soon as I turned around I saw a man with a gun. I felt the bullet shatter through my ribs and lodge deep in my heart. My last gasps filled my lungs with agony—agony that drove away my exhaustion, my hunger, the grass, the sun, the sounds of birds, until nothing remained.

When I came to, I felt torturing heat, pain unlike anything I had felt before. I was shrouded in darkness, except for the light of a fire roaring beneath me. I expected it to leap up and consume me, but it was confined in a stone fireplace. I needed to yelp out in pain, but I was unable. My body was gone, and with it, my hunger, voice, and spirit. Only my head remained, crucified onto a wooden plaque nailed into the fireplace mantelpiece. All my muscles, my jaw, nose, ears, were fixed in place by some mystic force. Anguish filled what was left of me, an empty husk of a head, and with no way to express it, I began to suffocate.

My eyes soon adjusted to the darkness and I saw that I was in a human's house, caged away from the open world. Although I had seen glimpses of the strange, jagged homes of human beings when venturing far from the savanna, being inside one for the first time I saw how unnaturally horrifying it was. The walls and furniture, all made of deadwood, were carved into alien shapes, unlike anything nature was capable of producing. I smelled not the air of the serengeti but a strange musky scent that gave me a blistering headache.

I was surrounded by death. Elephant and boar tusks were mounted on furniture, and the dried skin of a zebra was stretched on the floor in front of the fireplace. Teeth and skulls of gibbons and baboons, meticulously polished, were displayed in glass casings. To my sides on the mantelpiece were the heads of a lioness, gazelle, and buffalo, all condemned to my same fate. Their bodies were gone, heads frozen and nailed to a plaque. The fire cast dark, dancing specters of body parts onto the dim walls. I could not bear to see more. I needed to shut my eyes, but they were fixed wide open.

Time ceased to exist without the sun and moon. Even after the fire died, the pain of being fixed in place kept me from sleeping. After what may have been a day, or an hour, I finally heard heavy steps, and a man came in.

I recognized him as the hunter who shot me. He rekindled the fire, and I was again driven mad by the heat. He began polishing my teeth with a foul smelling substance, scraping off layers of blood and years of hunts.

I had never seen a human up close before. Their eyes and noses are weak, plastered on their flat faces, serving almost no purpose in survival. Their teeth are small and dull. The hunter was an exceptionally poor specimen. He was old, wrinkled, and should have been eaten by a predator long ago. His thin, gray hair barely covered his temple, which was covered in cancerous spots. His eyes were dulled by age and framed by thick spectacles. His teeth were thin and frail, lining a gap-tooth smile as he carefully brushed oil into my fur.

Initially I thought this man, having hunted so many beasts, was a great predator. I soon learned he is actually timid and weak. Aside from smoking tobacco from his pipe and drinking whisky to dull his already weak senses, he busies himself by reading in a rocking chair in front of the fire. He must squint his eyes to read by the light of the fire, and his hands tremble, barely able to hold a book steady. If the room had just a few windows, his eyesight would be better, and the smoke from his pipe would not cloud around and sting my eyes and nostrils. But he spends his days holed up in the darkness like a pathetic worm. Not once have I seen the presence of a mate or friend.

When the hunter is gone, and the fire beneath me is quiet, I am able to have quiet moments alone with my thoughts. When I was alive, being preoccupied with hunting and foraging, I never had time to engage in deeper thoughts. Now I am nothing but my thoughts, and as far as nature is concerned, I no longer exist.

I often think about my two cubs, who have surely been eaten by now. In this sense, my life has been a failure. The great lineage of my ancestors has ended with me. Perhaps I deserve this suffering. Maybe my comrades on the mantelpiece have failed in this endeavor as well, and we are here on tribunal, awaiting judgement from a decrepit man. But then again, life and death are natural. Animals must eat and be eaten. Even the death my two cubs will help birth new life. Have I not held the cycle of life and death in sacred respect?

Only humans live so far beyond their allotted time on earth, living in strange houses and squandering their years reading and smoking instead of gorging on their prey and producing as many offspring as possible. I have come to the conclusion that the hunter is delirious in his own way, with his constant drinking and smoking and loneliness. He mistakes his prey with companionship, which is why he must always surround himself with bodily relics of his hunts. Perhaps it is too late in his life to find companionship. If a younger, stronger human found him, they would most likely kill and eat him. It is a miracle he has lived to his age.

One day the hunter returned with the corpse of a crocodile. I admit I was quite impressed. The crocodile is the fiercest of all serengeti beasts, a behemoth that not even a leopardess like myself dares to approach. The crocodile, which the hunter laid over a thick tarp, almost stretched the length of the room. Just when I thought I could one day respect the man, he proceeded to behead the animal with a machete and toss the body away, saving only the head. He emptied out the head, replaced the innards with a strange, white, foamy substance, and left it to dry near the fire.

I came to a sickening realization. He did not hunt out of hunger or survival, but for sport. How could a creature of the earth so easily toss away another’s body? A body that could have fed my cubs, which could have decided the fate of a starving animal? I remembered the hunger I felt when I died, the kind of hunger that saps all energy but pushes you to take another’s life, lest you yourself collapse, barely conscious, while another animal is forced to eat you.

I hold in memory all the beasts I have killed, down to the look in their eyes as I closed my teeth around their necks, blood spurting, passing their life to me, until the day I myself may pass it to a stronger beast. I assumed my body was eaten by the man, but it was more likely rotting away somewhere, along with the bodies of all the animals in this house. Looking at all the tusks, bones, skins, and heads in the room, and I saw mountains of bodies, never able to pass the gift of life. I prayed that our bodies at least nourished the maggots and insects.

For the first time I felt the need to kill out of hatred. This man was not a creature of the earth, but a wicked fiend that sought only to steal and hoard life’s essence. As if nature heard my call, I was blessed with a miracle a few days later. The head of the crocodile was dried, and when the man began to nail in the crocodile next to me on the mantelpiece, each hammer stroke loosened the nails that held me in place. After nailing in his new victim, he returned to his rocking chair and began to smoke, unaware he had set in motion my opportunity for retribution.

Everytime the man rocks in his chair under me, it shakes the mantelpiece ever so slightly and I draw closer to my one and only opportunity for the kill. I must always be alert, eyes keen on my victim. Although I can feel the looseness of the nails, I cannot know for sure when I will be released. If fate is gracious, the man’s neck will be bare, and as I fall, my fangs will dive straight into it, or I will at least fall onto the back of the head, causing damage that will lead to his slow death. If fate is not gracious, I will miss entirely and fall into the fire, and I will finally be freed from this suffering.

Fueled by my new mission, the fire below does not feel as unforgiving, and the smoke from his pipe does not irritate me as much. The faces of my comrades next to me grow brighter with each passing moment, as if they know their salvation is at hand. And although I will never set foot on the serengeti again, it grows more and more vivid in my memories, knowing that if I succeed, the serengeti will be a better land for all life.

I pray that Mother Nature is sympathetic to my cause, and that I have Her blessing for the atrocious sin I will soon commit. I hope when he dies, the hunter will never be eaten, never pass his wicked life to another, and rot for a thousand years. The man sits under me, rocking gently in his chair. I can feel the nails loosen ever so slightly. I must wait for the opportune moment. Let me bring justice to the man who brought so much pain to the beasts of the land, or let me perish in flames!